Press

Return to the list of articles

THE CHERRY ORCHARD (People’s Light): Capturing the comedy, insight, and pathos of Chekhov

Debra Miller of Phindie

February 15, 2015

Completed in 1904, THE CHERRY ORCHARD, Anton Chekhov’s final dramatic work, is the most often staged of all Russian plays worldwide, and its production at People’s Light & Theatre Company (adaptation by Emily Mann) affirms why. Combining insightful socio-cultural farce with gripping human pathos, its dual nature as comedy and tragedy is captured in spades by director Abigail Adams and her extraordinary team of actors and designers.

Set at the turn of the 20th century, in the pivotal time that saw the decline of the aristocracy, the rise of the bourgeoisie following the abolition of serfdom in 1861, and the fulmination of the Russian Revolution of 1917, Chekhov’s story revolves around the auction sale of an aristocratic estate, with its extensive cherry orchard, to pay off the family’s delinquent mortgage and growing debt. Lyubov Ranevskaya, the widowed mistress of the house, returns from five years in Paris with her daughter Anya, after having spent lavishly there on the latest French fashions and on the “worthless scoundrel” she loves. She is met back home by family, friends, and servants, who catch up with each other on marriage proposals, deaths, travels, finances, and bygone days—most notably the impending loss of her ancestral property and the changing socio-political direction of her homeland.

Academy Award nominees Mary McDonnell (as Lyubov) and David Strathairn (as her brother Gayev), and Barrymore Award winner Pete Pryor (as Lopakhin, the entrepreneurial son of their former serf), lead a stellar cast that emphasizes the comedy but empathizes with the strife, futility, and nostalgia for a past that cannot be sustained, and the suffering of an underclass that will at last emerge from its past oppression. McDonnell is magnificent as the epitome of the out-of-touch aristocratic landowner, cheerfully fluttering around the stage, gushing about her childhood memories of the cherry orchard, grieving for the loss of her son, charmingly tossing off cruel remarks to others with a careless candor (“You’ve gotten old and ugly!”), refusing to deal with the inevitable, and in denial about the reversal of fortune that has befallen her, her family, and her entire class, while awaiting a deus ex machina that never comes. Strathairn is equally loquacious in his soliloquies and cavalier in his insults, and childishly dependent on his 87-year-old manservant Firs (the superb Graham Smith, who will break your heart in the final scene), until he is so thoughtlessly left behind with nothing, after having “lived too long.” Pryor embodies the understated sarcastic wit, business acumen, and growing materialism of Lopakhin with his signature comedic timing and a hilarious slapstick episode (choreography by Samantha Bellomo), in which he becomes the mistaken victim of a blow to the face.

Among the consistently fine supporting cast, Olivia Mell (McDonnell’s real-life daughter) glows as Anya, representing a privileged younger generation that is not so attached to the past and is more open to change; Sanjit De Silva is convincingly serious as Petya Trofimov, Anya’s love interest and the idealistic “perpetual student” committed to a socialist future; and Mary Elizabeth Scallen mesmerizes as Charlotta, the girl’s eccentric governess with a German accent and a never-ending repertoire of magic tricks. Peter DeLaurier is a delight as the financially-drained elderly nobleman Boris Simeonov-Pishchik, who falls asleep mid-conversation, but maintains his optimism by borrowing money from everyone around him, and Luigi Sottile is appropriately unlikeable as Yasha, the obnoxious, unethical, and self-centered young servant who accompanied Lyubov on her trip to Paris.

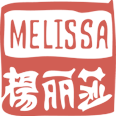

The top-notch acting and direction are enhanced by a splendid artistic design, with lavish period-style costumes (Marla J. Jurglanis); an expansive set (Tony Straiges) that evinces the grandeur and history of the manor house and estate; beautiful lighting of interior and exterior, day- and night-time scenes (Dennis Parichy); and haunting original music provided by Melissa Dunphy (as both composer and in her role as the Musician, performing live on violin).