Press

Return to the list of articles

iHamlet by The Philadelphia Shakespeare Theatre, and: Kill Shakespeare: A Live Graphic Novel by Revolution Shakespeare (review)

Justin B. Hopkins of Shakespeare Bulletin

June 1, 2015

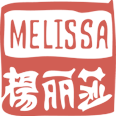

The annual Philadelphia Fringe Arts Festival gathers an eclectic collection of talent from around the Philadelphia area in a celebration of experimental performance. The 2015 Fringe featured several productions based on Shakespeare’s texts, and I was able to attend two. Melissa Dunphy is far from the first woman to play Hamlet, even for the Philadelphia Shakespeare Theatre (local audiences will recall Maria Tuomanen’s fine performance in 2011). However, Dunphy must be among the few(er) who have delivered the part in under an hour. As the audience entered and surrounded the flat, nearly bare stage on three sides, Dunphy sat—sometimes straight up, sometimes slumped—on an upholstered chair in front of a gold-gilt mirror, playing a black viola. Her hair bleached blonde and close cropped, her bottom lip pierced, she wore sneakers and a black suit jacket. On a crescendo, she stood, turned, and stepped forward, announcing in her natural Australian accent: “The time is out of joint. O…” (1.5.189). But instead of continuing on into “cursèd spite,” she jumped back three scenes. “O that this too too sullied flesh…” (1.2.129) she began, then checked herself: “Sullied flesh?” After performance reviews

unsuccessfully consulting several of the books carelessly piled on a table in the corner, she produced an iPhone and said, “sullied flesh” to it. Siri replied, “Did you mean solid flesh?” I laughed, enjoying the joke on the whole solid/sullied controversy (though I’m a sullied man, myself).

What followed was a fifty minute flurry of highlights from Hamlet—or, rather, Hamlet—frequently punctuated by that phrase, “The time is out of joint” (1.5.189), and transitioning into other lines that begin with “O”—“O god, a beast that wants discourse of reason…” (1.2.150), “O villain!” (1.5.106), “O what a rogue and peasant slave am I!” (2.2.527), and so on. “Collaged” by South African playwright Robin Malan, this adaptation—not to say abbreviation—of Hamlet cut to the core of the character, shedding everything else Shakespeare wrote to accompany him. No more supporting cast, though Dunphy interacted with the audience

at times, addressing us as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, joining us on “Here’s mettle more attractive” (3.2.99), and stabbing at us on “Dead for a ducat!” (3.4.23). No more plot, though there seemed some method to the madness: surges of chaos and subsidences of calm. Hamlet revels in self-revelation, and this production allowed unimpeded insight into his psyche—or her psyche, rather, since Dunphy did not try to masculinize her performance in any way.

For example, in one quick sequence, she stripped off her coat, revealing tattoos of birds on her shoulders and arm, and angrily spat, “Denmark’s a prison” (2.2.239). Then quickly she segued into a frustrated, “And yet within a month” (1.2.145), before pulling a wallet from her pocket, flipping it open to show the photo inside, and demanding, “Look here upon this picture” (3.4.52). The frantic flailing from one thought to the next perfectly captured Hamlet’s fragile yet powerful mind: an antic disposition indeed, rather than merely in seeming. Again and again she returned to the phrase, “Denmark’s a prison,” a refrain reflecting her feelings of captivity and suppression. She ended abruptly. Throwing her hoodie off, she sat, and spoke about “special providence” (5.2.157), repeating, “The readiness is all” (5.2.160). Then, once more, she cried, “The time is out of joint,” but this time she got out “O cursed spite” (1.5.189) before suddenly miming being stabbed in the belly. Clutching her gut, she looked at the audience and gasped, “Fuck!” and collapsed, shaking, dying.

I missed “the rest is silence” (5.2.300). I missed Claudius, especially his speech in the chapel. I missed Ophelia, especially her “What a noble mind is here o’erthrown” speech (3.1.149-60). I missed Polonius and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and the First Gravedigger. Confession: I didn’t miss Gertrude much—never cared for her. But none of those characters were the point. This was a psychological portrait of narrow focus, yet great depth. In the program for the production, director (and designer) David O’Connor called the adaptation “more efficient and

richer” than the full-length version. O’Connor claimed, “in cutting the other characters, we don’t just get a shorter version. Because in Hamlet, the external conflicts are not the stuff of the play. [. . .] In this play, the real battle is internal” (Program). I don’t know that I quite agree. Hamlet is not only Hamlet; the prince requires the court for complete context and full realization. But as an exercise in efficiency and concentrated perspective, the execution was well rich enough.